Etchings Indigenous: Black and Sexy

Etchings Indigenous: Black and Sexy

Etchings Indigenous: Black and Sexy

(anthology)

Ilura Press, Melbourne, 2010

ISBN: 9781921325137

PB, 176 pp

There is an underlying tension in this collection of work by Aboriginal writers and artists, that reflects the real tension between Aborigines and the wider community in Australia. This wider community is certainly not homogeneous, with its sometimes disparate ethnic groups, the result of waves of migration from different parts of the world. I myself was part of such a wave in 1955. As a society, we manage to eventually feel fairly comfortable with each ‘new’ ethnic group that comes to this country. We accept the differences or cease to notice them.

But what of the Aborigines who, more than two hundred years ago, witnessed a small invasion of Europeans, an invasion that resulted in the Aborigines being eventually classed as the outsiders? What must it be like to be made to feel an alien in your own land? This collection goes some way to answering those questions. Etchings Indigenous is edgy, with the underlying anger, sadness and frustration of many of the contributors coming through their stories, poetry, art and photography. Although there is no single philosophy expressed, I was left with a feeling of loss, washed in some cases with hope.

When I arrived from the Netherlands, it was ‘only’ seven or eight generations after the First Fleet had arrived, yet the plight of the original custodians of this land was well and truly entrenched. At primary school in NSW we learned about this “sorry race” that was “so far behind White society”. We were taught that by the time we were adults there probably would be few, if any, ‘true’ Aborigines left.

When I was at university (1967 – 1971), I was part of a group raising funds for scholarships for Aborigines to study at university and to give financial support for Aboriginal families to help their children to continue their high school education to even make it possible for them to qualify for university education. The 1960s and ’70s saw a turning around of attitudes, with the referendum and other symbols of a change in consciousness in Australian society. Etchings Indigenous reflects much of this, including the fact that many of the contributors have university degrees and some of them teach at universities.

Storytelling is an integral part of Aboriginal culture, irrespective of the many language groups which exist. As with European, American, Asian and African sagas, myths, fairytales and legends, Aboriginal stories are designed or have evolved to entertain, inform and educate. The stories in this book are clearly aimed at informing and educating us, the non-Aborigines. In some cases they also entertain, as in ‘White Ants’ by Ali Cobby Eckermann, in which an old woman gets the better of a bureaucrat who is hedged in by rules and procedures.

Some of the pieces aim mainly to inform, such as the interviews with Nathan Lovett-Murray (with Coral Reeve), John Harding and Kim Kruger (both with Christine Ward), and the reviews by Janelle Moran of music by Geoffrey Gurrumul Yunupingu and Coral Reeve of music by Corinthian Morgan (Mr Morgz). Janelle Moran, Coral Reeve and Christine Ward formed the editorial team for Etchings Indigenous.

Janelle Moran also reviews two books: Listen deeply, let these stories in (by Kathleen Kenmarre Wallace with Judy Lovell) and You call it desert – we used to live there (by Pat Lowe with Jimmy Pike). Both Listen deeply and You call it desert are about loss of traditional lands and heritage and the journey to reclaim them. Both books also contain photos and/or art which are integral to the telling.

There are contributions included that show us that Aborigines often have to deal with the same issues that beset others in the wider community. The essay by Jirra Lulla Harvey accompanying Bindi Cole’s photos of the ‘Sista Girls’ shows a world that is both familiar to us and different. The Sista Girls are Aboriginal men living in Tiwi, who identify themselves as women, often since childhood. As in our wider community, they find themselves accepted by some (mostly family) and rejected by many. Their stories are in many cases heartrending and the photos are beautiful.

Some of the work is angry, such as ‘Everyday Heroes’ by John Williams-Mozley:

Where are all the monuments to our heroes

whose words and deeds inspire us?

…

I look around and all I see

are epitaphs to your obscenities,

countless unmarked gravestones,

where huge monuments ought to be.

The effects of the forced and unforced breaking up of families are also explored in story (‘Meeting my Dad’ by Katie Wyatt) and poetry (‘The Highest Branch’ by Jannali Jones). Tales of loss and heartbreak. ‘Meeting my Dad’ deals, in part with the consequences of White bosses taking sexual advantage of (in many cases perpetrating rape on) young Black women and the questions surrounding whether to pursue ‘justice’, even if that were available.

While all the written and visual art in Etchings Indigenous is by indigenous people, it is not all identifiably Aboriginal. ‘Fifty, female and taking flight’, by Shirley Morgan, is about someone discovering the joys of travelling to a foreign country and getting hooked on the experience. It reads like a travelogue and could have been written by someone from any culture. This very fact gives power to the whole collection, because it highlights that the works lie along a continuum, with ‘Fifty, female and taking flight’ and ‘Life Resumed’ (anonymous) at one end and the poetry of Brenda Saunders at the other end; the story ‘Distance’ by Tony Birch lies somewhere in the middle.

What of the other stories along the continuum? Some, like ‘Local Knowledge’ by Barry Cooper and ‘Men’s Camp’ by Henry Dalgetty, illustrate a meeting of cultures. ‘Distance’, by Tony Birch, seems to be about a man looking for his roots; he could be Aboriginal but we’re not told, allowing the possibility that he is ‘everyman’. The short soliloquy ‘Up the Road’, by playwright John Harding, deals with the anger about a brother who died at the hands of the police.

The poetry also falls at various points along the continuum and I have mentioned some examples already. ‘Rainbow of Eternity’, by Nellie Green, includes the following: “I cried as I recalled the Human / Neglect of all those Sacred things / We were meant to Protect …”; it ends with: “Whilst amongst it all, we Stand / Still so hopeful for the Perfect world / We so Desire”. Dennis Fisher, in ‘What’s Australian?’, asks “Is an Australian a person who speaks a language that comes from another country?”. He also expresses hope: “I have hope / … that doesn’t come from England” (in ‘Comes From’). Brenda Saunders in her three poems alludes to the visual arts as giving expression to the country. Poet and artist Paula Miller-Reeve starts ‘Tread Softly My Friend’ with: “I’ve walked these lands before / through the eyes of my ancestors”. In her poems, Ali Cobby Eckermann deals with issues of bullying, abuse and alienation.

I found that some of the poems had an immediate impact on me with their very accessible imagery and easy metre. Others I had to read a number of times in order for their messages to come through to me, but the effort was well worth it. As with some of the stories, not all the poems seemed essentially Aboriginal.

All this brings up the question for me of ‘What is Aboriginal writing or art?’ Does the ethnicity or provenance of the creator of the work define it as such? I think the answer lies more in something less easily defined that comes through. Some of the work in this collection feels as if it is born out of the creators’ immersion in the culture or, at least, out of a strong connection with it. Other stories come out of a yearning for what has been personally or culturally lost and which will perhaps never be recovered. And some of it calls from an even greater distance – a wish to be part of that culture, having been brought up outside it.

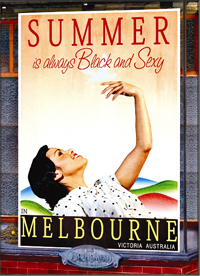

The posters by Bindi Cole appear to express a complex reality: Aborigines having over the years attempted to take on European culture for the sake of acceptance, or ‘Whites’ having used (more accurately misused) images of Aborigines to indicate an acceptance of the ‘Blacks’ by inserting those images into very non-aboriginal contexts. This misappropriation of images is also symbolic of Whites’ attitudes that the people themselves could be appropriated to White needs. The posters (one of which forms the cover of the book) mimic early theatre posters and I find them disturbing, because of the juxtaposition of the images and words used. ‘Summer is always Black and Sexy’ is one example of this; another is ‘Dante, 50 mysteries of how to breed a race of white Aborigines’. The artist seems to be pointing to the discomfort of so many Whites around Aborigines and the way they have been treated (and are still being treated). I can hear these people declaiming that some of their best friends are Aboriginal or, at least, that they know some Aborigines and they’re actually alright.

The book contains some beautiful artwork. I have mentioned Bindi Cole’s posters and photographs (all in colour). There is more recognisably Aboriginal art (in black and white) by members of the Centre for Koorie Education at Goulburn Ovens TAFE and the (colour) dot paintings of Nellie Green. Not being familiar with the traditions behind or the meanings inherent in Aboriginal paintings, some written explanations accompanying these would have helped. Without this, the paintings are beautiful and interesting but tell me no more than this surface viewing, with a few exceptions where wildlife is portrayed. On the other hand, the photos (some colour, some monochrome) by Wayne Quilliam, Elizabeth Liddle, Steven Rhall and Bindi Cole are more easily recognisable because I am more familiar with this form of expression, as would most people looking through this book. It is another example of Aboriginal artists taking up non-traditional art forms which speak more easily to non-Aboriginal viewers. This is not unique to Aboriginal art. For instance, I find Japanese theatre difficult to understand (even when translated) as there are traditions I am not privy to. This is also the case within Western society, where various people do not understand ballet or symphonic music or jazz or rap.

There is much in the poetry and storytelling in Etchings Indigenous that speaks to us because of our shared humanity. We can feel outrage and sadness or hopelessness, not because we know anything about Aboriginal culture but because we are witness, through these works, of terrible deeds perpetrated by one group of people against another. The ‘sorry’ speech by Kevin Rudd in the Federal Parliament in February 2008 had little to do with apologising to Aborigines for what we or our predecessors or forebears might have done to them. It was more an expression of our shared humanity and an attempt to express an understanding. Etchings Indigenous stimulates our own understanding of that shared humanity. It is not about a chosen group of Aboriginal artists and writers trying to teach us their culture, but to have us see them as fellow travellers who also bleed when they are pricked.

© 2010 Daan Spijer

[to receive an email each time a new review is posted, email me: <daan [dot] spijer [at] gmail [dot] com>]

CLICK HERE to download a formatted PDF of the above post

CLICK HERE to download a formatted PDF of the above post

See more of Daan Spijer’s writing and his photos at Seventh House Communications

See more of Daan Spijer’s writing and his photos at Seventh House Communications

[…] here at my kitchen table, dog prostrate at my feet, I have spent quiet days immersing myself in Etchings Indigenous: Black and Sexy, a project from Ilura Press. I’ve read it through several times and contemplated the stories, […]

Pingback by From the Kitchen #44 « Thinking Allowed — March 26, 2010 @ 11:36 am