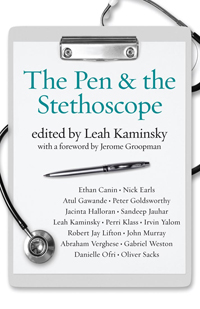

The Pen and the Stethoscope

The Pen and the Stethoscope

The Pen and the Stethoscope

Ed: Leah Kaminsky

Scribe Publishing 2010

ISBN: 9781921640735

$32.95

240 pp

This is a strange collection – an anthology of stories and essays linked only by the fact that all the writers are, or once were, doctors. The nine non-fiction pieces hang together through their subject matter; however, only a few of the six fictional short stories obviously owe something to the medical training of their authors. Nevertheless, every piece entertains or informs or both and I enjoyed them all.

I will talk about the fiction offerings first.

In ‘We are Nighttime Travelers’ (by Ethan Canin, a writer first, a doctor second and only for a short time) the narrator tells us, “this is a true story … I have been more or less faithful to Francine since I married her” and, “… when I recall my life my mood turns sour and I am reminded that no man makes truly proper use of his time.” It is indeed a love story, of two old people and an attempt to find meaning and expression of that meaning.

‘Dog1, Dog 2’ (Nick Earls) is a clever, creepy story about medical research and identity. It is masterfully written, taking the reader through changes that are so subtle, you almost miss them. Once a doctor, Nick Earls is now a successful writer.

Peter Goldsworthy is both a practising GP and a writer. ‘The Duty to Die Cheaply’ is about a doctor forced to spend much of a plane flight sitting next to a corpse. A funny, sad, reflective story.

Jacinta Halloran (GP and writer), in ‘Finding Joshua’, examines the constant self-examination that goes on in the mind of a mother (a doctor) whose teenage son took his own life. She describes the half-life she and her husband now exist in, the ‘mausoleum’ they now inhabit. Feelings of hopelessness and guilt and the question ‘why?’.

‘Tahirih’ by Leah Kaminsky (a GP and editor of this collection) is a beautifully crafted story of an abused woman who has escaped from persecution in Iran; because of his beliefs, her husband was executed. The narrator is a doctor who reflects on Tahirih’s ordeals, her faith, her patience and her strength.

John Murray’s ‘Communion’ ends the book. A story of a life ending, it explores the lives of those around the dying man, from the point of view of his daughter. The language sets it in rural USA but it deals with universal issues of love and relationship, self-denial and service. John Murray works in child health programs in developing countries.

The essays occupy the first 133 pages of the book. They start with a fascinating examination of how difficult it is to introduce simple, cheap, life-saving (and money-saving) reforms in hospitals. In ‘The Checklist’, surgeon Atul Gawande chronicles the resistance that hospitals have put up against the introduction of a five-point checklist for the handling of patients on life support in intensive care units. Part of the antipathy comes from the resistance to changing the doctor-nurse relationship, part of it from the notion that something so simple cannot make a difference and part from hospital administrators not wanting to change how things ‘have always been done’. It seems that logic and clear benefits are not enough to bring necessary change, despite the fact that in one hospital alone the implementation of the checklist had, in one year, saved eight lives and saved two million dollars.

‘Falling Down’, by cardiologist Sandeep Jauhar, is a brief memoir from the author’s days as a hospital intern. It is from his book Intern: a doctor’s initiation (2008, Farrar, Straus and Giroux).

‘Index Case’ is an account by Professor of Journalism and of Paediatrics, Perri Klass, of his “annual pediatric krudd” (the winter cough he developed each year as a paediatrician). On one occasion it turned out to be much more serious than he had thought, with far-reaching consequences.

‘The Nazi Doctors’ is a series of extracts from the book Nazi Doctors: Medical Killing and the Psychology of Genocide (1986, Basic Books) by Psychiatry Professor Robert Jay Lifton. The work is based on his interviews with doctors who were involved in the Nazi genocide. It is an important work, though (because of the subject matter) difficult reading.

Professor Danielle Ofri’s ‘Intensive Care’ (from her book Singular Intimacies: becoming a doctor at Bellevue – 2003, Penguin) is a funny, insightful, heartfelt reportage of her interactions with an attending specialist in a hospital ICU and her discovery of his humanity. This is a wonderful demonstration that non-fiction, if well written, can be every bit as gripping and moving as fiction.

Professor Oliver Sacks is known to most people as the author of Awakenings (1999, Knopf Doubleday) and The Man who Mistook his Wife for a Hat (1970, Touchstone). ‘The Lost Mariner’ comes from the latter. It is an examination of “what sort of world, what sort of self, can be preserved in a man who has lost the greater part of his memory, and, with this, his past, and his mooring in time?” The patient in this piece remembers nothing past 1945 and thinks he is nineteen years old, even though he is a bearded old man. It certainly does bring up existential questions surrounding the role of memory in shaping who we are.

‘Bedside Manners’ by Professor of Internal Medicine and of the Theory and Practice of Medicine Abraham Verghese, is a reflective piece about the changes in hospitals, from ‘old’ diagnostic tools and skills to the reliance on big machines and laboratory tests. He reports one student telling him that “a man with a missing finger must get an X-ray before anyone will believe he has only four”. The author mourns the passing of the testing of medical students on real patients with real conditions (“it is too subjective”) and the loss of these valuable skills. He says that “it is a skill [students] should cultivate, not to replace technology but to allow them to use technology judiciously and to ask better questions of the tests”.

Gabriel Weston is a part-time ENT surgeon. In ‘Beauty’ she talks of the ‘beauty’ of surgery, its straightforwardness, its neatness. Then she recounts an awful incident in which this straightforwardness all came apart.

Professor Irvin Yalom is a psychiatrist. His piece ‘Do Not Go Gentle’ is a wry tale of his getting involved with a patient’s infidelity by agreeing to store a bundle of old love letters. The consequences are told with humour and self-examination.

Despite my misgivings voiced at the start, this is a thoroughly informative and entertaining collection. I enjoyed reading through it a second time and will probably bring it down off the bookshelf again in the future. Other works by these authors also make good reading and many of the works in this anthology are good introductions to these.

© 2011 Daan Spijer

[to receive an email each time a new review is posted, email me: <daan [dot] spijer [at] gmail [dot] com>]

CLICK HERE to download a formatted PDF of the above post

CLICK HERE to download a formatted PDF of the above post

See more of Daan Spijer’s writing and his photos at Seventh House Communications

See more of Daan Spijer’s writing and his photos at Seventh House Communications